By David Broughton – June 22, 2020.

When it comes to sports facility security and sanitation, no idea is too far-fetched as companies flood the market with products and services aimed at lowering a facility’s potential to spread disease.

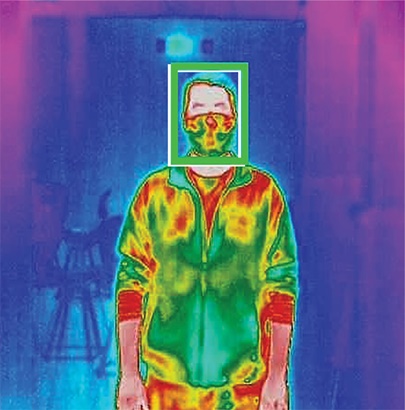

Look no further than the skies, where drones are being hawked as a fast, efficient way to spray disinfectant throughout the seating bowl. Thermal detection equipment goes beyond identifying those with higher body temperatures to also make sure fans maintain social distancing. Upgraded ventilation systems improve air quality and reduce the chance for germs to spread.

While facilities will be following security and sanitation guidelines from state and local health departments before they reopen, the crisis has produced many new concepts almost daily. It’s just a matter of how much buildings want to spend beyond the guidelines to increase the confidence level of fans.

“We’re all going to be our own risk manager,” said John Petrone, president of Petrone Risk, a consulting firm that works with sports facilities.

Earl Santee, founder and senior principal at Populous, said in a recent webinar hosted by the Stadium Managers Association that his firm’s research finds 52 potential touch points along an attendee’s game-day path, “and every one of them has to have the same amount of care and attention.”

Here are some of the latest technologies and nontraditional approaches being hawked and how they are being positioned to help with security and sanitation.

Security

Thornton Tomasetti is known in sports circles primarily as an engineering firm that has worked on dozens of venues over the years, including the ongoing construction in Seattle of the NHL’s newest arena.

But the company’s protective design and security services division, whose portfolio includes embassies, airports and FBI offices, has created a digital platform for the post-COVID live-event experience that the firm’s associate principal, Bill Edwards, calls “virtual queuing.”

It starts with the purchase of your ticket on an app, where you are presented with a liability waiver that tells the team that you acknowledge you are going to be in a crowded building and that the team will not be held liable if you contract a virus at the venue. “In legal terms, it’s a safe harbor for venue owners and operators,” Edwards said.

The app provides gate and security line assignments, and a range of times to arrive. Upon arrival, fans will have their temperature taken, be asked health screening questions and then have their ticket scanned.

Then the confluence of security and hygiene takes over.

“You will be given a BLE-enabled tag or lanyard or bracelet that you will be required to wear while you are in the venue,” Edwards said.

BLE is short for Bluetooth Low Energy and the technology tracks the movement of fans. The app will guide the fans to their seat, locate their assigned restroom and tell them how to order food. The BLE bracelet can notify stadium staff if a fan attempts to move to a different section or tries another no-no, such as entering the gift shop without reserving an assigned time.

Edwards said the technology can be integrated with a team’s current ticketing and security platforms. He would not disclose pricing, but said that it will be dynamic, as venues can choose a la carte which of the different behaviors they want tracked.

Patriot One Technologies and LAFC are forming a consortium of sports security professionals to evaluate and pilot new physical security technologies, including those focused on health. Dubbed “The Stadium & Event Safety Strategic Alliance,” the two plan to use the club’s stadium as a testing ground for new security concepts.

Through a series of recent acquisitions, Vancouver-based Patriot One has evolved from a weapons detection company to a shop whose platform is driven by algorithms based on data from a network of hidden sensors that can detect concealed weapons and crowd disturbances from parking lots to the seating bowl. It can also detect thermal elevated body temperature, lack of social distancing and perform contact tracing, which can help identify those who may have come in contact with an infected person. The company’s system is in use at Great American Ballpark.

Incident management tech companies with sporting events on their résumés, such as Everbridge and Juvare, also have added contact tracing to their suite of offerings. Each company has worked on behalf of municipalities and their emergency personnel at recent Super Bowls and World Series monitoring things like traffic and road closures, as well as suspicious individuals and packages.

Despite the pledges of what the technology can deliver, the vendors’ biggest challenge will be to find teams and venues willing to pay for the latest offerings at a time when the pandemic has ravaged their balance sheets.

“Everything costs money,” said Petrone, whose firm is overseeing the emergency preparedness plans for Churchill Downs and Pocono Raceway and has 20 other sports clients at different stages of similar evaluations. “Adding staff and technology costs money. This hits every level of the organization.”

Sanitation

Sanitation efforts have received such heightened awareness that the U.S. Green Building Council, best known for its LEED certification for facilities that do the best with energy consumption and the environment, now give credits to buildings undergoing the certification process for following green cleaning best practices.

Air quality is one area getting a big focus as facilities explore technology that filters out more hazardous particles such as germs carrying COVID-19.

Fairfield, Conn.-based AtmosAir offers a system that relies on a technology called bipolar ionization. It integrates into existing HVAC systems and produces ions that attach to particles like COVID-19, making them bigger and easier to filter out.

The system was incorporated into the $185 million renovation of Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse and is in the Texas Rangers’ yet-to-be-christened Globe Life Field. The technology was deployed last year in U.S. Bank Stadium at a cost just over $1 million for a 10-year contract that includes service. Clean air was one of the reasons the stadium was awarded the highest level of LEED certification.

Approximately 20 other stadiums and arenas, including multi-team buildings such as Staples Center, TD Garden, Wells Fargo Center, Little Caesars Arena and Gillette Stadium, have had the AtmosAir system installed. Executives from Gensler and Skanska, who are well known in the sports design and construction world, are among the company’s advisory board.

When it comes to sanitizing spaces, Chicago’s Soldier Field was ahead of the game, not as much by way of technology but in its relationship with a vendor. Prior to the pandemic, the stadium had already been using World Cleaning Services to clean its premium areas, according to Moira O’Connor, the stadium’s director of operations.

“While typically focused on hospitals, World Cleaning has given us an advantage having them as our building partner during the pandemic,” O’Connor said.

That includes supplying the stadium with two Karcher misting machines and medical grade disinfectant. The misters use electrostatic to help sanitizers and disinfectants attach themselves to surfaces. The process is cost efficient because less liquid is wasted and it can be applied faster than conventional methods, according to hygiene reports. The machines are in high demand and sources told Sports Business Journal they can sell for approximately $5,000.

Clorox makes a similar machine that is used in several venues, including Boston’s Fenway Park. The company has been running its cleaning and disinfecting product plants 24/7 to catch up with demand.

Perhaps the most head-turning concept for sanitizing venues is the use of drones.

Buffalo-based EagleHawk debuted its patent-pending, disinfectant-spraying drones in May at Sahlen Field, home of the Class AAA Buffalo Bisons. Since then, KeyBank Center and Upstate Medical University Arena in Syracuse, N.Y., and more than a dozen NFL teams and Division I college programs have invited EagleHawk to their venues to demonstrate the technology.

Co-founder and CEO Patrick Walsh graduated from the Rochester Institute of Technology and earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and an MBA from Rollins College in Florida. Prior to founding EagleHawk in 2016, he had spent most of his career with Lockheed Martin working with advanced thermal imaging systems for fighter aircraft and helicopters. He launched his business to survey water leaks at large facilities, then moved into agricultural fungicide spraying. He now has a fleet of more than 20 drones.

“You need a license to spray fungicide, but as of now, if you are disinfecting you don’t,” he said. “The capacity and spray droplets are different. Plus, the change in elevation of seats makes mapping the venues challenging.”

Walsh said a staff of four people with two drones could disinfect a 19,000-seat arena in 2-3 hours and a stadium in 3-4 hours, a fraction of the time and cost of what teams are spending now to do the work by hand. He said the drones also provide more thorough disinfectant coverage.

During the first phase of flying in a sports venue, the drones are tethered as they digitally map the building; sensors prevent the machine from colliding with structures. Part of that tether system is a hose that continuously feeds the disinfectant solution to the drone.

Walsh would not disclose how much it costs to hire his company but said the expense would be quickly recouped. He said he’s been working with the EPA and various New York government offices to finalize all approvals.

“The department of transportation said, ‘You want to do what?’ So it’s pretty exciting to not really be doing things by the book, but actually writing the book with the authorities!”